The area around Pendle Hill has a rich and vibrant heritage, that has seldom been explored.

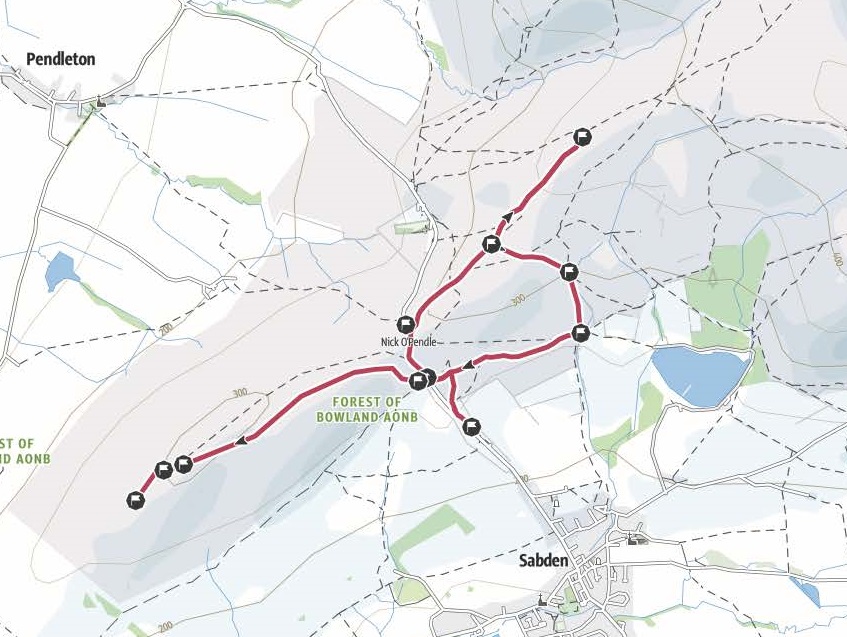

We have created a short walk around the Nick of Pendle that explores these archaeological sites. This is a map of the walk route as seen on the Outdoor Active map.

The first evidence of people living in Pendle area comes from the Neolithic. The lack of evidence for earlier people, in the ages called the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic, doesn’t mean no one was living in Pendle, it is more that the remains left behind in these time periods are often hard to find or not well preserved. Prehistoric people did not have metal, which means that archaeologists only have wood (which is easily biodegradable) and stone left to find. There could have been settlement of Pendle early in the Neolithic, but there is very little evidence to prove this.

Neolithic means “New Stone Age” neo meaning new, and lithic meaning stone. There are some good examples of Neolithic pottery in Clitheroe castle museum.

The Neolithic culture was the first to develop farming, so they are considered the first farmers in Britain. They ploughed fields to grow grain and kept animals like cows and sheep. They also are known for building the first burial monuments for their dead. Pikestones monument on Angelzarke moor, Chorley, is probably the best local example of this kind of Neolithic monument.

Bronze Age people also left behind a kind of burial monument called a Barrow. These were made by digging a circular ditch and heaping earth up in the centre. In the North of England you also get Cairn monuments. These represent what was left when a barrow constructed of stone and earth erodes away. On Pendle Hill we have both of these kinds of monuments. Because monuments like these left a mark on the landscape, they often have local, and later, legends attached them to explain their existence.

The Devils Apronful is a Bronze Age monument, and the first stop on the walk. The stones visible here represent two barrows. Barrows of this type are often found in cemeteries, grouped together. These cairns have never been formally excavated, and it’s a mystery to what they may contain. Barrows in Lancashire often have inverted funerary urns inside them. Perhaps this barrow once had an urn inside.

The Devils Apronful is a Bronze Age monument, and the first stop on the walk. The stones visible here represent two barrows. Barrows of this type are often found in cemeteries, grouped together. These cairns have never been formally excavated, and it’s a mystery to what they may contain. Barrows in Lancashire often have inverted funerary urns inside them. Perhaps this barrow once had an urn inside.

The Devils Apronful likely represents two barrows close to each other. The first of these is a ring bank cairn, about 10m wide. Most of the original stone has been disturbed to build a modern cairn on the edge of this monument, but the large built structure is still intact.

Image: The Devils Apronful stone scatter

The second barrow is an 18m wide embankment. This represents the disturbed cairn and its hollow centre; this is near a modern cairn erected by out- of-work dry stone wall builders in the 1920s.

It was clearly important to the people who built the barrows that they are visible within the landscape. Pendle Hill was a rich ritual landscape with lots of activity high up in these moorlands.

These barrows have a local legend attached to them. In this particular legend, the devil was walking from Accrington with an apronful of stones to throw at Clitheroe castle. He stepped from Hambleden hill to Craggs farm, were he left these footprints on a rock. When he was walking over Pendle Hill, his apron string broke. The rocks he was carrying spilt on the ground, forming the Devils apronful mound. This is a variation of very common legend about barrows. They are often associated with devils or giants, who create these barrows accidentally when their plans are foiled. It has been suggested that this legend represents the local peoples dislike of the castle, and the people who built it.

Near to the site are the Deerstones footprints. Supposedly left by the devil, this is possibly an example of rock art. It is probably Bronze Age and linked to the building of the barrows in this area. Feet in rock art is very common in Bronze Age Scandinavia, suggesting a possible cultural link. Alternative theories suggest the 'footprints' are hand carved, or are a natural geological or glacial feature.

Worsaw Hill also has a Bronze Age burial monument at its peak, at the south-east side, which can be seen from the ridge of Pendle Hill. There was possibly also a Bronze Age settlement here, there are visible earthworks which may suggest some kind of hill fort. Very little is known about this archaeological site. However, the density of barrows in Pendle suggests that this was an extremely sacred space. The people of the Bronze Age who created these prominent barrows would have taken time and skill to construct them, showing their importance as an addition to the landscape. Barrows can often be seen from the site of other barrows in the area. It makes sense that the barrow on Worsaw Hill can be seen from the site of Apronful Hill.

Jeppe Knaves Grave, near the Nick of Pendle is also likely to be a Bronze Age cairn, that possibly started out as a barrow. The body would be placed on the earth first, and then the mound created by digging a ditch piling this earth on top of the body. This particular cairn may date to much earlier than the Bronze Age. The large stones used in the construction of this monument suggests it may have an early origin as a Neolithic passage tomb. This monument is quite degraded, which means that precise dating of it is hard, especially as it has never been the subject to an archaeological excavation. This barrow has an engraving on one of the larger rocks that says “Jeppe Knaves Grave”. This was carved by local boy scouts in 1960s.

Jeppe Knaves Grave, near the Nick of Pendle is also likely to be a Bronze Age cairn, that possibly started out as a barrow. The body would be placed on the earth first, and then the mound created by digging a ditch piling this earth on top of the body. This particular cairn may date to much earlier than the Bronze Age. The large stones used in the construction of this monument suggests it may have an early origin as a Neolithic passage tomb. This monument is quite degraded, which means that precise dating of it is hard, especially as it has never been the subject to an archaeological excavation. This barrow has an engraving on one of the larger rocks that says “Jeppe Knaves Grave”. This was carved by local boy scouts in 1960s.

Image right: Jeppe Knaves grave.

The local legend here is that the barrow is the burial place of Jeppe the Knave. Jeppe was a man of noble birth who was beheaded for theft in 1327. The local parishes of Pendleton and Wiswell could not agree on who should have the responsibility of burying the body. To solve this problem, Jeppe was buried in un-consecrated ground on the border between these two parishes. There is some evidence that this legend is based on a real person. The name Jeppe Curtys first appears in local records in 1342 in documents about land boundaries between Wiswell and Pendleton. However, there is very little other evidence to support the idea that Jeppe was buried at the barrow.

The local legend here is that the barrow is the burial place of Jeppe the Knave. Jeppe was a man of noble birth who was beheaded for theft in 1327. The local parishes of Pendleton and Wiswell could not agree on who should have the responsibility of burying the body. To solve this problem, Jeppe was buried in un-consecrated ground on the border between these two parishes. There is some evidence that this legend is based on a real person. The name Jeppe Curtys first appears in local records in 1342 in documents about land boundaries between Wiswell and Pendleton. However, there is very little other evidence to support the idea that Jeppe was buried at the barrow.

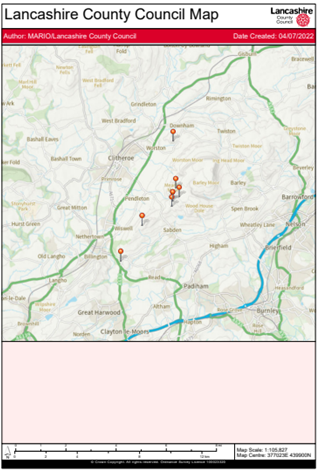

Map right: Location of some of the Cairns and barrows in the Pendle Hill Area. They are often found close together, or within viewing distance of other barrows.

After the Bronze Age came the Iron Age (approximately 750 BC to 43 AD). In Pendle, Iron Age people built a kind of monument called a hill fort. Hill forts are large circular earthworks. These were constructed on a natural hill, and then surrounding it with deep mounds and ditches. Archaeologists are not sure why Iron Age people built hill forts. Some archaeologists think they were built for defence, with the ditches as a kind of fortification. Others think that hill forts were gathering places in the landscape, and would have been poor at defending from attack. The best example of a hill fort locally is Portfield Hillfort near Whalley, although the history of this site goes back much further.

T

Despite the lack of relevant finds from the site, the Iron Age was most likely the time when this hill fort was at its peak. Portfield hill fort originally had ditches and ramparts, a common feature in other Iron Age hill forts in Britain.

This hill fort has been badly damaged over the years, particularly by water pipeline work in the 1960s and 70s. In 2022 a team from UCLAN took part in the most thorough excavation of the site in its history. More information on this can be found at-

**insert weblink to the uclan site page when it goes live.

This shows, particularly with the recent excavation of a C17 limekiln, that Portfield was occupied and used by humans for thousands of years.

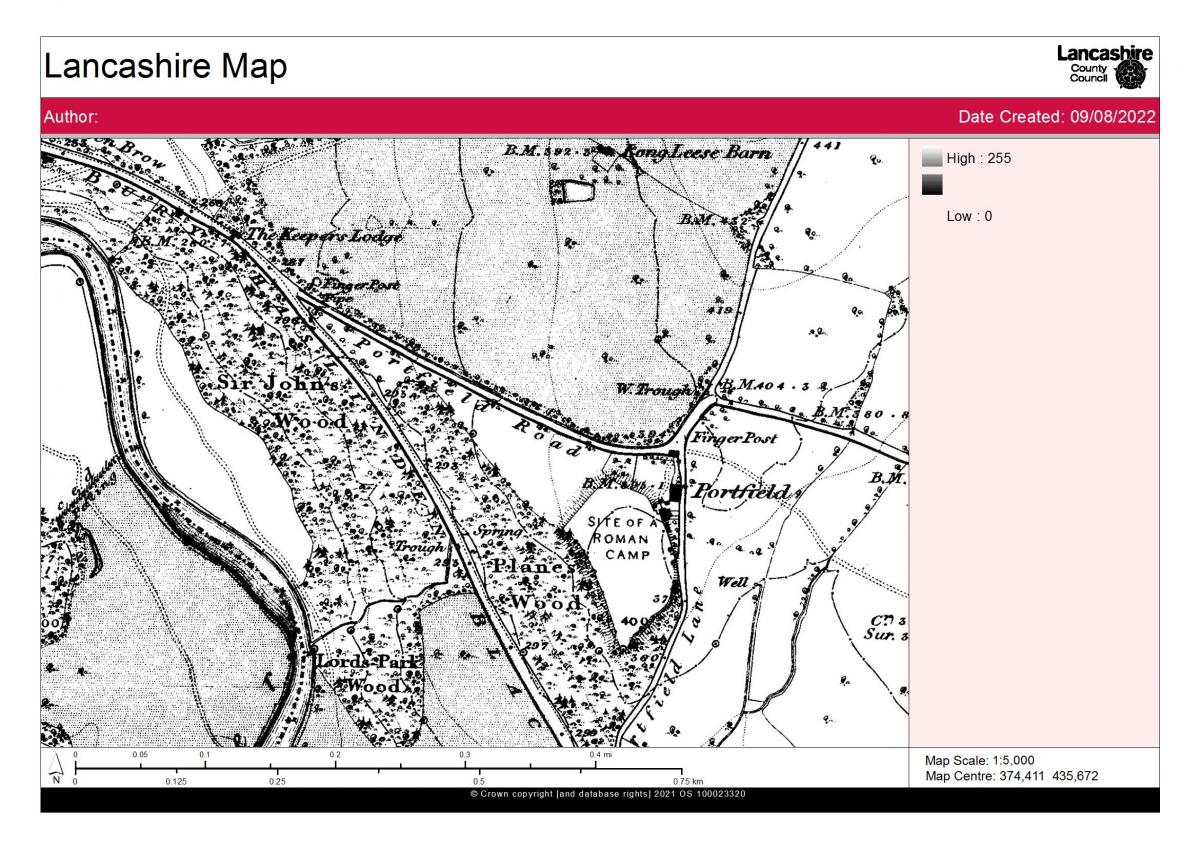

The image to the right is from the 1840 original OS map showing Portfield hillfort as “Site of a Roman Camp”. While there might have been Roman activity at Portfield, the fort is mostly much earlier.

Hill forts are quite mysterious to archaeologists. It’s not clear why hill forts were built, or what they were used for. They tend to not have a water source within their ditches, meaning that they would not have been effective at withstanding a long siege, or to be convenient as a place where people lived full-time. Some suggestions for what hillfort were used for include grain storage, as animal pens, and as refuges during times of conflict and raiding.

In the Roman period AD43 – 410), Pendle was not heavily occupied. Most of the Roman activity was focused on Ribchester fort. This fort was called Bremetennacum Veteranorum. The Ribchester Museum website can be accessed at Ribchester Roman Museum - Ribchester Roman Museum (ribchestermuseum.org) for more information.

A Roman road runs along the bottom of Pendle Hill along the Ribble valley, from Ribchester and then terminating at York.

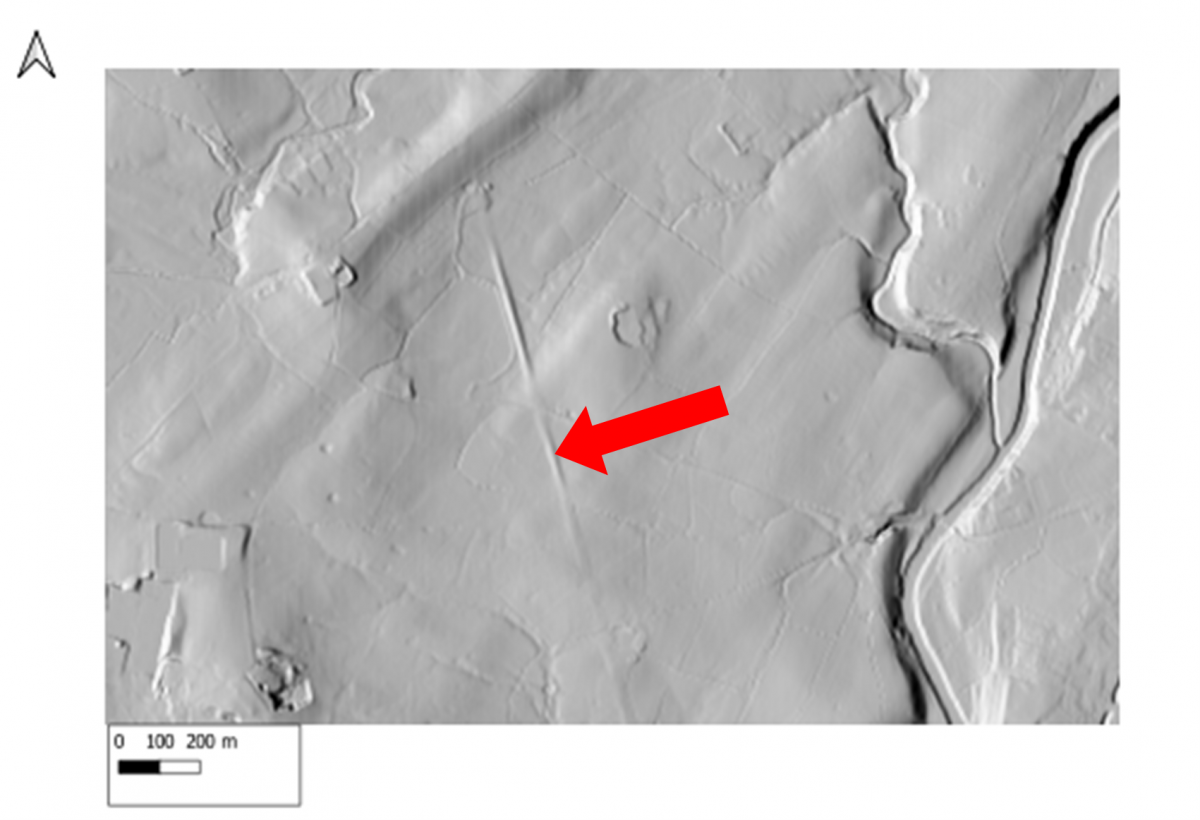

Image right: LIDAR Image showing the path of the Roman Road. Map from DIGIMAPS. The red arrow shows where the road is visible.

Looking down into the valley, you might be able to see the path of the Roman road. This section of road ran from Ribchester to Elslack, through the outskirts of what is now Clitheroe. This road crosses the Calder near Whalley, and turns slightly at Downham. It has a Margary number of 72 A, which is how Roman roads are named and classified.

A section of this road was dug by the Ribble Valley Archaeology group near the village of Rimington. They uncovered significant amounts of the road surface itself, along with a few pieces of pottery. Roman roads are often quite empty of archaeological finds, as the people using them are always moving, not spending enough time in one place to deposit materials.

The image right is an aerial photograph showing the earthworks at Bomber Camp and beneath it, volunteers working with the Pendle Hill project team.

In 2022, more of this Roman road was excavated by PHLP and Eocosult with the help of volunteers, near Salthill in Clitheroe.

**Add details when report is published.** Sadly no conclusive evidence of this being a Roman structure was found.

This road would have been extremely remote. The road ran across moorland, with no nearby forts or settlements. It must have felt extremely lonely to travel along. The nearest contemporary site is Bomber Camp near Gisburn.

This enclosure was probably used as a farmstead by the Romano British people. This shows that while Pendle was quite quiet in the Roman period, people were still here and were probably engaged in farming. It can be seen today as a rectangular enclosure made of ditches. When it was excavated in 1940s, it was reported that samian wear (Roman pottery), a corn grinding stone and a sword were found. It is located so far from the road because roads are dangerous places with bandits and travellers. Despite being contemporary with the road, Bomber Camp was always extremely small and extremely remote.

After the Romans came the Anglo-Saxons (410-1066). There is very little Saxon archaeology in the Pendle area. However, the phrase “Pendle Hill” is Saxon. Pen was a pre-Roman local word for a hill. The new Saxon peoples added the extra “Dhyll” at the end.

In the Norman period/early medieval period (after 1066), the Forest of Pendle was granted to the De Lacy Family. This family were granted the Blackburn Hundred by the king and allowed Clitheroe castle to be built. The De Lacy family used the area almost exclusively for farming cattle in large enclosures called Vaccaries. This was a very profitable way of farming at the time.

Vaccaries were an early way of dividing land. They were specific land divisions for breeding cattle, granted by the King to local landowners, as a way of ensuring loyalty. Most of the vaccaries in Pendle were owned by the De Lacy family.

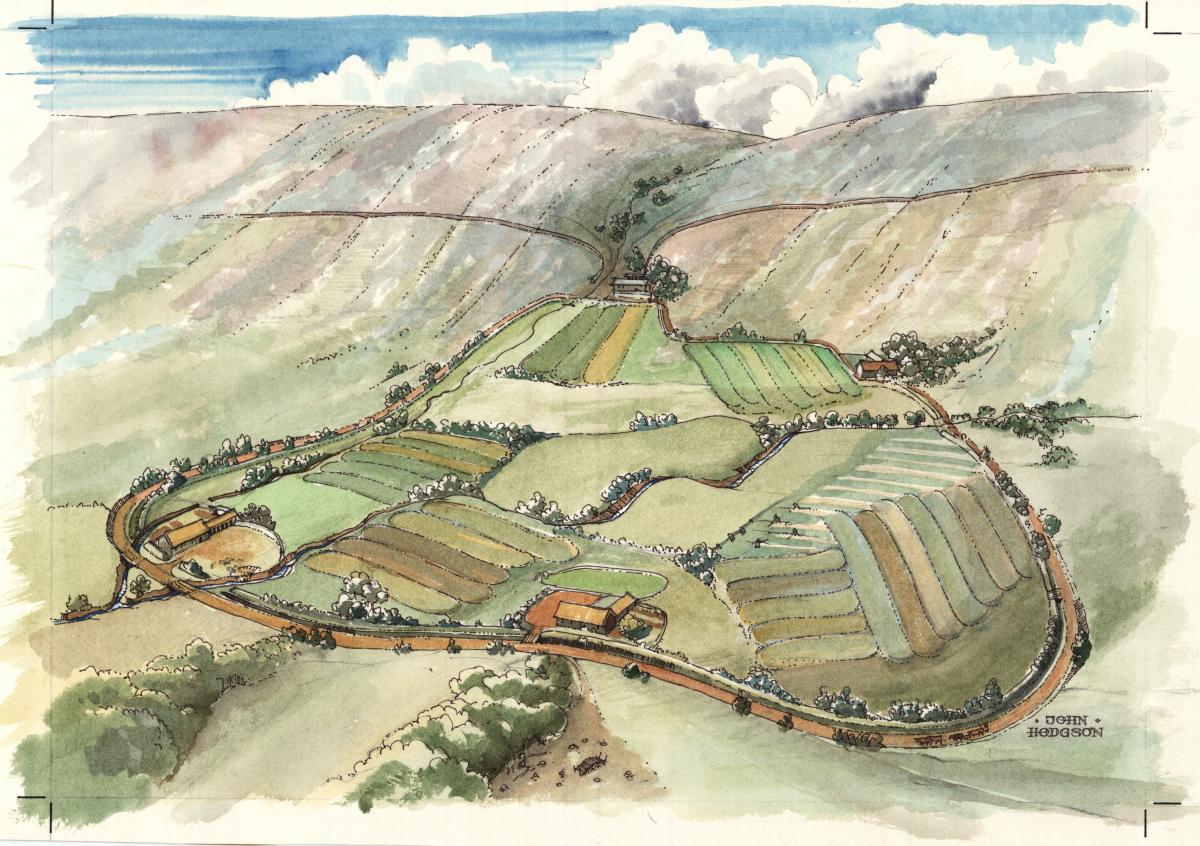

This is an illustration of Sabden Fold Vaccary by John Hobson.

There were at least 5 vaccaries in the Pendle area, each with about 900 animals. They were kept by a cow keeper, who paid 3 pounds a year for the privilege. This payment was called Lactage. Lactage comes from the Latin word Lact, meaning milk. This was because the Cow keeper was allowed to keep and sell all the dairy products from the cows as payment for the upkeep the cattle. In time, these massive farms became sub divided. They later became “Booths”, or farms let to tenants. These farmsteads became the foundation for many of the villages in the area today.

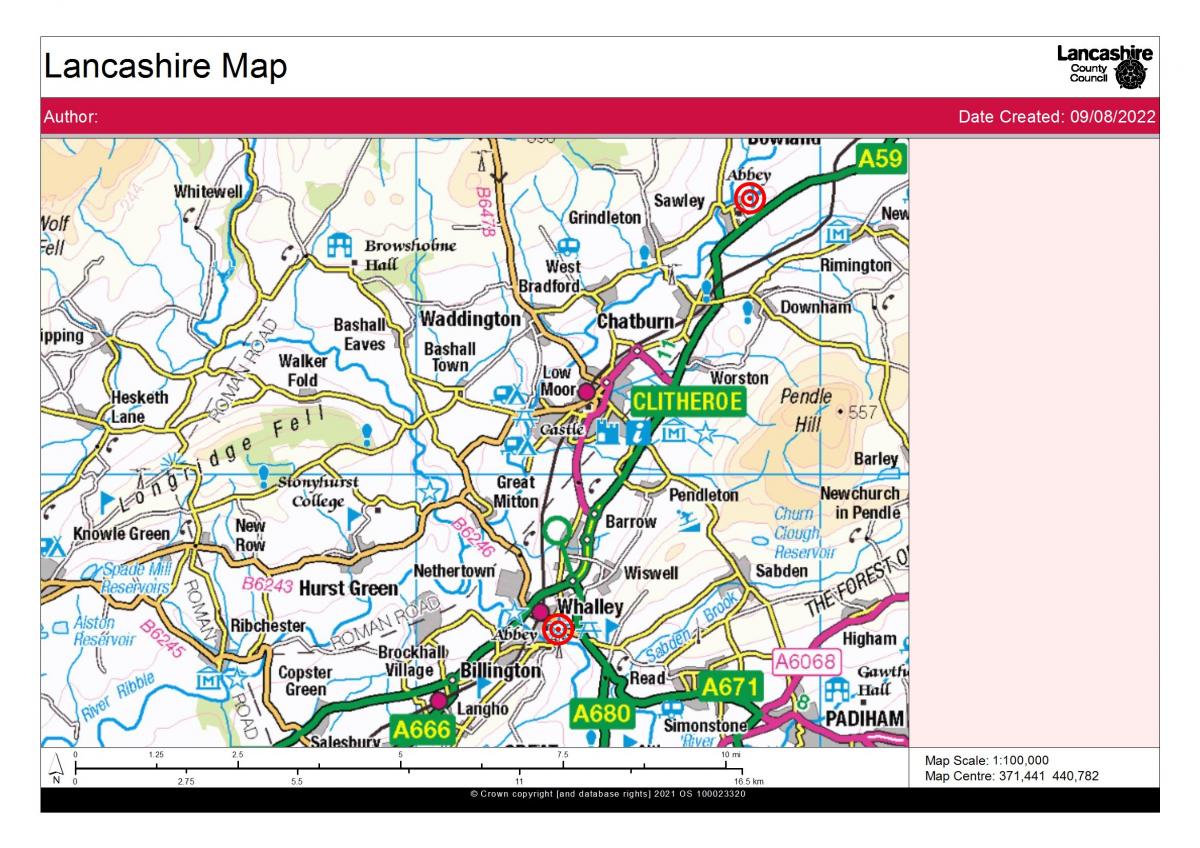

The map shows how close the two Abbeys were. The top dot represents Sawley Abbey, and the bottom dot is Whalley.

Sawley Abbey was prone to flooding, making growing food difficult. Sawley therefore struggled to be self-sufficient, having to buy in most of its food supplies, when most monastic houses grew all their own food. It also had to absorb the cost of lodging travellers along the main road for free, a problem Whalley did not have to manage. This predicament was made worse by the fact that Sawley was attacked by Scottish invaders several times.

Sawley Abbey is notable due to its extensive earthworks. Monasteries often had large amounts of land attached to them. These earthworks most likely represent the gardens, stock pens, and other enclosures that were vital for monastic farming. Sawley also has a holy well within these earthworks. Holy wells were very fashionable in mediaeval England and served as a draw for pilgrims to the abbeys.

The abbey is unusual due to its extremely short nave. The nave is a middle part of the church where the congregation gather. It is probably very short as Sawley was always a poor abbey. The contrast this, Sawley had a very wide transept, the cross shaped sides of the church. This is because this part of the Abbey Church was a much later addition when the abbey had more money. This makes the church of Sawley abbey a very unusual shape.

Sawley ceased to function as a monastery during the Dissolution of the monasteries in 1535. However, it briefly reopened during The Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536. For more information on this visit History of Sawley Abbey | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk). This was a rebellion of Catholics in the North of England. Despite this, Sawley was empty by 1537. The high-quality stone with extensively reused in the building of Worston and the other nearby villages. If you walk through Worston today, you may be able to spot some of this reused stone.

The first archaeological exploration on this site was in 1848 by the landowner, Lord De Gray. The site was then cleared and partially rebuilt in the 19th century. Today, the site is grade 1 listed, due to the extensive survival of the medieval stonework.

In the early modern period, the most documented account locally is the Lancashire Witch trials and the famous Pendle Witches (1612). Archaeologically, the best evidence of this is the recent Uclan and PHLP excavation of the possible site of Malkin Tower, the supposed meeting point of the accused. You can find out more information on this by visiting- insert web link here.

During the industrial revolution, Pendle was a hotbed of reformers. More evidence on who these people were can be found at the Pendle Radicals Project at Pendle Radicals – Extraordinary stories of radical thinkers. On Pendle Hill itself, a relic of these reformers can be seen at the Chartists Well. The chartists were campaigners for social conditions and working rights. This well was a meeting place where radicals would gather to speak to the people.

In the 21st century, the hill is best known for walking and other outdoor pursuits. It is located in an ideal countryside setting with spectacular views.

For further reading visit:

- Kenyon, D. The origins of Lancashire. Manchester University Press. 1991.

- The Devil's Footprints and Other Folklore: Local Legend and Archaeological Evidence in Lancashire TOPICS, NOTES AND COMMENTS David A. Barrowclough & John Hallam. 2008.

- Dixon J. ‘Journeys Through Brigantia Vol 1 Walks in Craven, Airedale and Wharfedale’ by Aussteiger Press, Barnoldswick, 1990.

- Barrowclough, D. Prehistoric Lancashire. 1st ed. Stroud: The History Press, 2008.

- Mitchell, W. R., Bowland And Pendle Hill, Phillimore & Co. Ltd., Chichester, West Sussex, England, 2004

Weblinks

- Sawley Cistercian abbey and associated earthworks, Sawley - 1015492 | Historic England

- History of Sawley Abbey | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk)

- Heritage Gateway - Results

- History of Sawley Abbey | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk)

- Bomber Camp Romano-British farmstead and associated enclosure, Bracewell and Brogden - 1013817 | Historic England

- Portfield hillfort, Whalley - 1013608 | Historic England

- North Lancashire - Nikolaus Pevsner - Google Books

- Jeppe Knave Grave on Pendle Hill - Red Rose Collections from Lancashire County Council

- Lancashire Magic & Mystery: Secrets of the Red Rose County - Kenneth Fields - Google Books

- Jeppe Knave Grave on Pendle Hill - Red Rose Collections from Lancashire County Council

- Lancashire Magic & Mystery: Secrets of the Red Rose County - Kenneth Fields - Google Books

- The Devil's Footprints and Other Folklore: Local Legend and Archaeological Evidence in Lancashire on JSTOR